by Xinhua writer Gao Wencheng

For years, some Western politicians and media have been pushing a rhetoric: China is driving developing countries into a “debt trap.” But a new report from London-based charity Debt Justice found the real story looks very different.

Covering 88 economies, the research disclosed that between 2020 and 2025, lower-income economies send 39 percent of their external debt payments to commercial lenders, 34 percent to multilateral institutions, and just 13 percent to Chinese public and private lenders. In other words, the bulk of the burden lies elsewhere.

The report pointed to striking examples. Mining giant Glencore refused to grant Chad any debt relief. After four and a half years of negotiations, Zambia has still to reach a deal with some private creditors, including Britain-based Standard Chartered. In Sri Lanka, Hamilton Reserve Bank has rejected the bondholder restructuring and is continuing to pursue a court case in New York state.

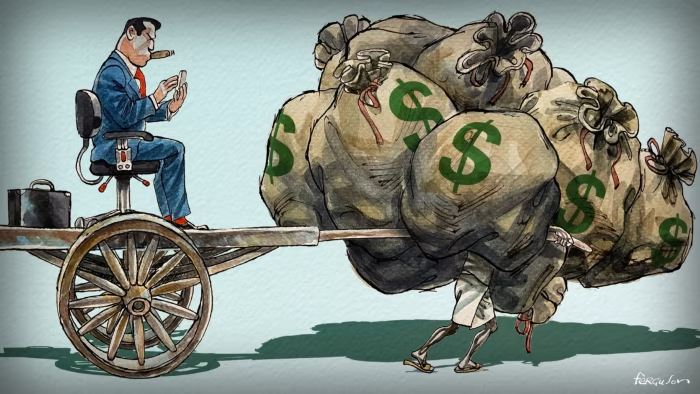

These creditors, largely Western, have adopted a hard-nosed and profit-first approach. As Tim Jones, head of policy with Debt Justice, put it, “Western leaders blame China for debt crises in Africa, but this is a distraction. The truth is their own banks, asset managers and oil traders are far more responsible.”

The real fault line is not just the size of debt but its terms. Unlike China’s “patient capital,” which emphasizes long-term development, Western commercial lenders and multilateral institutions often prioritize short-term gains. Their loans come with high interest rates, rigid repayment clauses, and sometimes political strings attached. This combination creates a cycle of dependency and financial vulnerability — the true trap that many developing nations struggle to escape.

This is hardly without precedent. The Global South has long lived with the consequences of Western financial orthodoxy. In Latin America, the Washington Consensus of 1989 forced governments to privatize state assets, deregulate economies, and liberalize trade and finance in exchange for loans.

Far from fostering prosperity, these policies hollowed out economic sovereignty and fueled social unrest. No wonder Honduran Vice Foreign Minister Gerardo Torres has said, “for decades, Western nations have imposed their financial criteria through loans that never led to true development.”

Breaking free from this cycle requires more than debt write-offs, and it demands diversified and sustainable growth. That is where China has focused its efforts.

Across Africa, where the “debt trap” narrative is most loudly repeated, Chinese financing has helped build and upgrade nearly 100,000 km of roads, more than 10,000 km of railways, and close to 100 ports. These investments lay the groundwork for connectivity, industrialization and long-term growth. African leaders have made the point clearly: China’s role is that of a partner, not a predator.

At its core, the “debt trap” debate is about more than finance. For decades, a Western-dominated debt system has constrained developing economies and curtailed their right to chart their own path. China’s model of cooperation, by contrast, points toward breaking those chains and opening new pathways for growth.

Ultimately, the question is not just about debt, but about who gets to set the rules of development in the 21st century, and whose voices are heard in shaping those rules.

If there is a genuine trap, it is the persistence of old narratives that deflect responsibility and obscure the structural inequities of the global financial system. Only by changing those narratives can space be created for fairer and more sustainable alternatives. Enditem

Source: Xinhua

Share Us