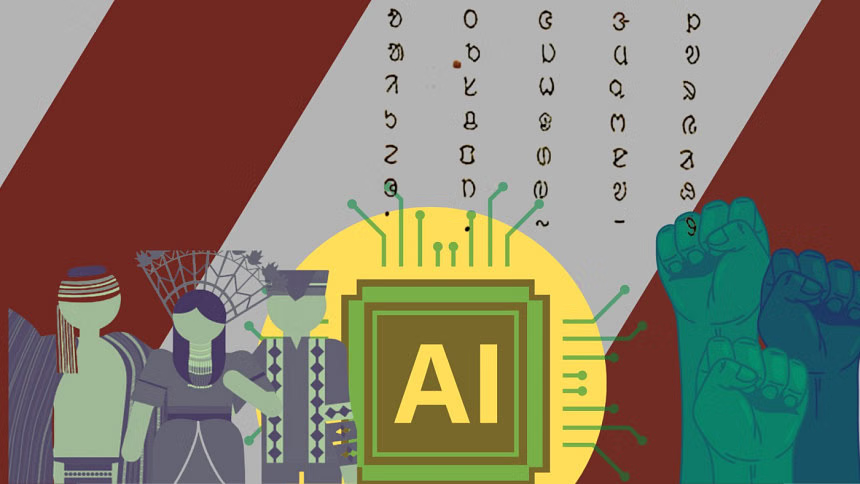

The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples this year is focused on the impact of artificial intelligence on indigenous rights, identities, and cultural and linguistic identity. AI is essentially a set of regulated algorithms, governed by global power structures and colonial legacies. As a result, existing AI models tend to obscure or misrepresent the knowledge and voices of indigenous communities. Consequently, such discriminatory AI models contribute to marginalisation and dispossession of indigenous societies.

Dr Maneesha Perera and others (2025) reviewed research on indigenous knowledge and AI, published between 2012 and 2023. They found a substantial body of work on indigenous knowledge offering a global indigenous perspective through intergenerational knowledge systems. At the same time, promising and aspirational research on AI has also been published. However, how these two strands of research intersect has not been discussed anywhere.

AI can play a crucial role in the development of indigenous knowledge. However, the potential risks to the indigenous knowledge systems must be considered as well. There is a risk of AI technology contributing to the erasure of indigenous cultural knowledge, committing biopiracy and violating the fundamental principles of indigenous data sovereignty. The expansion of AI technology could potentially exacerbate existing knowledge-based inequalities as well as structural discrimination.

In his address at the AI Action Summit 2025, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, “AI has gone from the stuff of science fiction to a powerful force that is transforming our world. Reshaping the way we live, work, and interact. Fuelling breakthroughs in education, healthcare, agriculture.” However, he cautioned that with this tremendous potential comes significant risks. “It (artificial intelligence) must accelerate sustainable development—not entrench inequalities,” he warned.

Colonial plunder and biopiracy

Indigenous communities have been integral to nearly all geographic identifiers and elements of national pride in Bangladesh. Yet, their contributions remain othered, mostly invisible, in the national narrative and consciousness.

For example, Muslin and Jamdani, the signature fabrics of Bangladesh, used to be weaved using Phuti karpas, a cotton variety cultivated by indigenous communities in the Bhawal and Madhupur region. The sesame molasses of Kushtia originated from indigenous jhum cultivation at the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Even the puffed rice used to weave Tangail sarees came from the indigenous villages along the Sherpur-Jamalpur border. Indigenous communities have suffered due to colonial plunder and biopiracy, often in the name of control, governance, research, development or management.

Indigenous peoples are arguably the most researched population in the world. Today, in the name of scientific inquiry, “bioprospecting” and genetic research, their biological resources and the traditional knowledge systems tied to these resources are being appropriated and stolen. Indigenous communities and their biological resources are the main target of biocolonialism. These resources are being taken without their consent and turned into patented commercial products.

Sporadic discussions have now emerged about how indigenous data and knowledge can be integrated, represented, and utilised within the broader AI ecosystem. The indigenous movement for information sovereignty has persisted for years, emphasising the right to own, control, and manage their own data. However, powerful states and corporations are steering the direction of AI use to incorporate indigenous knowledge without ensuring the active inclusion of indigenous communities in decision-making and governance. This glaring absence poses a serious crisis, undermining the free flow of indigenous information and the commitment to prior informed consent. Particularly, the use of indigenous knowledge, data, images, or identities in AI frameworks—without consent or conditional participation—creates a disconnect between the indigenous peoples and the technologies being developed.

Hence, it is imperative to ensure active and respectful inclusion of indigenous peoples at every level of AI development. If there are any discrepancies regarding any content, they can flag and resolve such complexities at the outset.

Decisions and governance over how AI models incorporate the genetic and cultural information of indigenous jhum crops and wild food sources must align with the traditional indigenous traditional systems. Otherwise, there will be a risk of unilateral commercial exploitation of these traditional knowledge systems. Enditem

Source: The Daily Star

Share Us